This post explores proposed BrowserID features that cannot be implemented with the current API. I’ll talk about four important features that would require a change to the API, and discuss the precise ways in which it would need to change.

The Current API

The current API for BrowserID is simple and delicious, consisting of two functions:

// attempt to get an assertion, possibly causing the user

// to be prompted. Options include:

// silent: boolean indicating whether the user should be

// prompted. when false, an assertion will only

// be returned if the user has chosen to "stay signed

// into this site" in a previous interaction.

// requiredEmail: When provided contains an email that the

// user must use.

// allowPersistent: give the user the option to "stay signed

// into this site".

//

navigator.id.get(<callback>, [options]);

// the user has indicated with actions in content that they

// wish to be logged out of this site, so if they've previously

// indicated they wish to "stay signed in", that preference should

// be cleared.

navigator.id.logout()An important subtlety is that there are actually two ways that one could apply the API:

- The simple usage: Call

.getwhen the user clicks a button, and after validating an assertion, set a cookie. Do nothing else. - The complex usage: Call

.getwithsilentset at page load when the user is not logged in. Call.getwithallowPersistentset when the user clicks a sign in button. Finally, invoke.logoutwhen the user indicates (with a click) that they want to logout of the site.

The former usage is extremely simple to explain and apply. The latter, however actually moves more control of session length into BrowserID which makes some valuable features possible.

The problems with the current API are twofold:

- the simple usage affords no way for a site to be informed that a user is already signed in, which prevents many UX optimizations, and user facing features.

- We are constrained by the simple path in what we can implement in BrowserID. For instance, if we sign the user in automatically as part of the verification process (when the site using BrowserID isn’t loaded), there’s no way to tell the site later that the user is already signed in.

BrowserID’s Missing Features

What are the concrete features that motivate this exploration and why do they matter?

Sign-out

Currently the only way a user has of meaningfully “Signing out of all sites” is to tell their browser to “Clear recent history” or to “Delete cookies and other site and plug-in data”. In my opinion, neither of the two user facing phrases clearly indicate the actual result in the way that a user can understand. Further, these actions are both meaningless and insufficiently granular: if the user wishes to “sign out everywhere” but not “remove all of my site preferences and data”, they cannot do this.

If sites don’t more frequently ask BrowserID “is the user signed in”, then we have no way of offering the user features like selective or global sign out of sites they use.

A Streamlined UX

The weakest point of BrowserID’s UX is when the user is required to go check their email and navigate back to the site they’re signing into. It is too hard to get from the link in your email back to the site that you started from in a signed in state. Currently we require the user to manually locate the tab where they initiated the action.

We’ve found via user testing that we can improve percieved experience for 8/9 users by having the link in email take the user directly back to the site that they were visiting

In order to make this streamlined UX work, the page using BrowserID must be able to detect that the user is logged in without prompting them.

Keep Me Signed In, For Real.

Depending on the security concerns of a given site, the period which you remain logged in can vary wildly. This is a typical tradeoff between security and usability, where a shorter authentication period can reduce user risk, but also requires the user to type their password more often.

In addition to the assessment of the site, optimal authentication duration should consider other factors related to the user:

- Is the user on a computer that is not her own?

- Does the user share her computer with others?

- Has the user recently (or ever) signed in with this computer?

- If the user is savvy, have they expressed an explicit desire about how long they wish to be signed in?

- Has the user expressed a desire regarding duration specifically for this site?

The work of considering all of these factors and building a perfect UX is hard. It’s also something that UX folks at mozilla are attacking head on. This work has the potential to further reduce the amount of work that sites must do while improving their security and usability.

A prerequisite for better authentication duration is for the user (via BrowserID or their browser), to have more control over session duration.

If sites were to decrease session (cookie) duration and get “silent assertions” from BrowserID more frequently, then the requisite hooks would be in place to implement the features discussed above: users will be able to feel like they’re “signed in” for long periods of time, but with a simple and intuitive action they’ll be able to prevent unwanted access to their stuff.

Better Browser Integration

A final area where any API that allows BrowserID to tell the page that the user has signed in or out is beneficial, is that it makes it possible for the browser itself to display such buttons in browser chrome, which can improve security (better phishing countermeasures) and usability (identical experience across sites).

The Requirements

The four features above distill into several concrete requirements that we can work from:

- BrowserID (or the Browser) must be able to send the page an event at any time indicating that the user is signed out

- BrowserID (or the Browser) must be able to send the page an event indicating that the user is signed in

- There should only be a single patterned way to use BrowserID that lets sites support central sign-out and streamlined UX without additional work. (Not a “simple” and a “complex” path).

The Problem

Making it so that BrowserID supports these features automatically, necessarily causes the implementation of BrowserID on your site to be more complex. To make this clear, let’s contrast informal flow diagrams of present API (in its simplest form), with a chart of what we would need to migrate to.

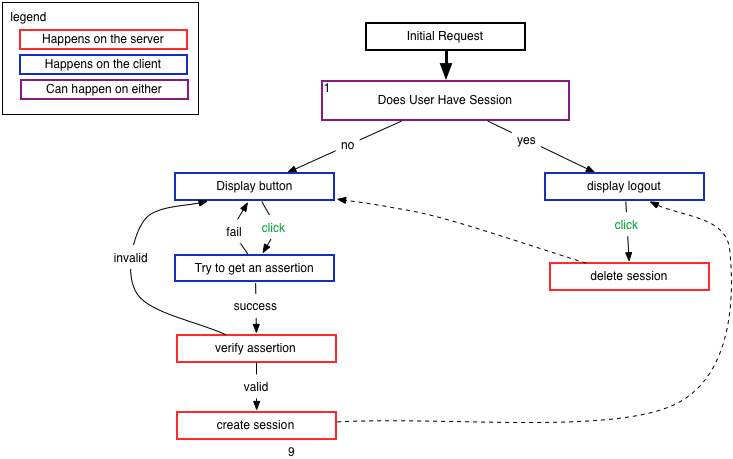

How We Implement BrowserID Today

The following diagram represents what how you implement the “simple API” of today on your site:

->  <-

<-

In this view, the notion of an “authentication session” is completely up

to the site to manage. If there is a cookie, for example, set by the

site that indicates that the user is logged in, that is always up to date.

Further, the site makes exactly one javascript call into BrowserID,

navigator.id.get() and that call is made at the time the user clicks on

a “sign in with BrowserID” button.

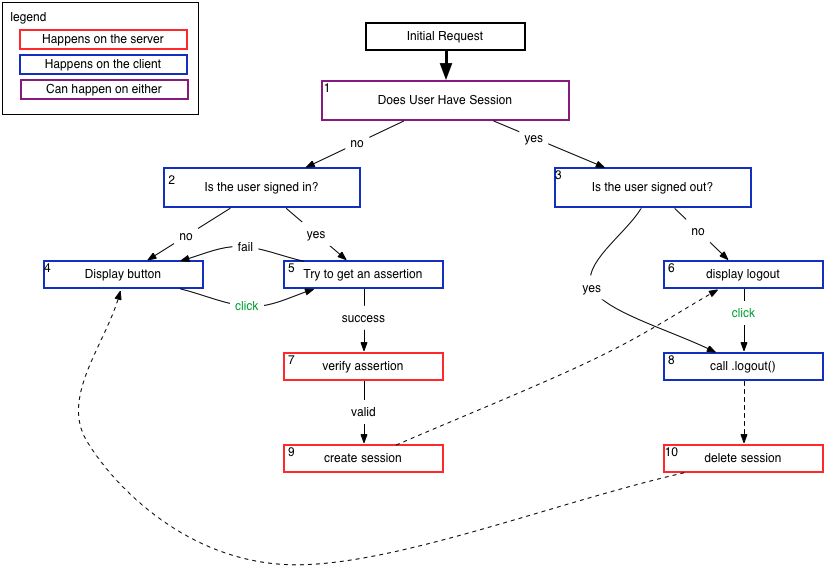

How We Might Change Things

What might things look like when a page implements a future version of BrowserID that supports the desired features discussed above?

->  <-

<-

The key difference in this diagram, is that at the time a request is issued to the server, the presence of a session cookie is insufficient to know if the user is logged in. Each page sent must double check that state to see if the user has signed in or out out of band.

Further, something that’s not represented in this digram, is that sites implementing BrowserID would have to subscribe to some sort of event, to check if the user signs in or out at some point after the page has loaded, either via browser chrome or otherwise out of band.

Challenges

There are a pile of issues to consider in moving to a more complex API for BrowserID, not the least of which is first run developer experience. The harder it is to apply BrowserID, the fewer people that will apply it. On the other hand, the features above are compelling and make rich user controls and a better experience possible. So let’s explore the different issues that should be considered when making this change.

Traditional Web Sites

A common trend in web development is single page web applications. Pages that serve a pile of resources at initial load and then provide most of their functionality using client side javascript, sometimes using features like pushState to preserve user expectations.

This model is interesting, but not all sites work like this. How specifically would a more traditional web application consisting of distinct pages apply this new BrowserID in the new model?

A typical pattern in a standard web application may be to have a single

page where users are directed to logout - /logout, and another where

they would be sent to sign in /signin. For sites of this type, they

could defer to their traditional session mechanism to determine if a user

was authenticated at the time they receive a page request.

If the user is authenticated, they would serve javascript that would

register with navigator.id in some fashion to be notified when a user

logs out. Upon detection of logout they would redirect the user to

the specified page from javascript.

The reverse is true if a user is signed out, javascript would have to be served with pages where the user is signed out that would detect and redirect to a sign in page when it’s discovered that the user is “signed in” with BrowserID, despite the absence of a site controlled session.

Some UX challenges that arises is clumsy page reload - how common will it be that a page is loaded, the user sees the content (customized for them), and then almost immediately that page is torn down, and another where they’re logged out is rendered?

Up Front Resource Costs

Until BrowserID is implemented natively, javascript resources are required to generate assertions. These resources are about 80k gzipped and minified, and are spread over four or five files.

In the present way that BrowserID works, these resources are lazily served at the time that a user authenticates (actually clicks the sign in button and sees the BrowserID dialog). In the new model, we would need to add an iframe to the DOM and load resources into that iframe at every page load.

This change may be distasteful to some users and we must figure out a way to minimize the cost. If the total cost were two new files whose aggregate gzipped and minified size were about 10k, would potential adopters of BrowserID still be off-put?

Assertion Generation Cost

Some alluringly simple API proposals for this new model suggest that we might implement this new model by simply firing a ‘login’ event at every page load where a user is signed in, having the payload of that event include an assertion.

The issues that exist with this proposal include resource cost discussed above, you would require the full 80k on every page-load, in addition to compute costs of generating an assertion.

For multi-page web applications, this added activity at page load time might contribute to a sluggish website feel.

A way around this problem would be to build the new API in a manner that performs a low cost operation to determine if the login state of the user is other than as perceived by the site, and only if required (upon further action by the site) do the work to generate an assertion.

Third Party Cookies Disabled

Many awesome browsers offer an option to users to disable third party cookies, that is cookies bound for domains other than that of the current webpage. Often privacy conscious users opt to disable third party cookies as they are most frequently used for user tracking and advertising.

Because of the way that we would have to implement the new API to support these features, this browser option will limit the success of user transparent assertion generation, and would require users with this option enabled to interact with the BrowserID dialog much more frequently.

Native browser implementations would solve this problem, and as the failure mode here is only an inconvenience, this is not a huge issue.

Required Email

A feature exists in BrowserID today to allow a website to specify the email address that it wants a user to verify. This feature is applicable in scenarios where the user has shared an email address with a site out of band, and the site wishes to use BrowserID to confirm that the user is actually in control of the address.

For this feature to function properly, one of two things is required:

- the site must be able to easily check to see if the address confirmed by an assertion is the one it wants

- OR, the site must be able to tell BrowserID which specific email it wants before any assertions are issued.

The complexity added by a new API with respect to this feature, is that

the API must have a convenient way to represent its constraints on the valid

email address before BrowserID does any processing. Presently, this

constraint is just an option to the .get call. Alternately, we might

choose to make it simpler for sites to check the email address on the

client, before verification.

This is not an intractable problem, but it will require careful API design.

Constraining Site Session Duration

Because of the way this would be implemented, signing out of BrowserID would probably sign you out on all sites which use it, and signing out of your BrowserID enabled email provider would probably sign you out of all sites where you use an email from that provider. This might be the right thing to do, anyway.

Nonetheless, this has UX ramifications that deserve careful attention.

tl;dr;

There are many interesting features that we could build into BrowserID. These features have the potential to make things safer and easier for users on sites that support BrowserID. To make them possible, we would need to make the BrowserID API more complicated to apply, which will likely hurt adoption.

Previously we’ve tried to have it both ways, to preserve the dead simple API that developers have praised - but to offer a more complex API that makes a better UX and important user facing features possible. This route is no longer useful, as we get the cost (we confuse people) without the benefit: the ability to improve UX and user control.

Next steps? Considering the issues above, let’s design the best possible API.