What programming language would make an AI coding assistant most effective? It’s a question that sounds simple but reveals a fascinating tension at the heart of how large language models learn to code. The answer isn’t just “whatever has the most training data.”

Boris Cherny’s Deliberate Choice

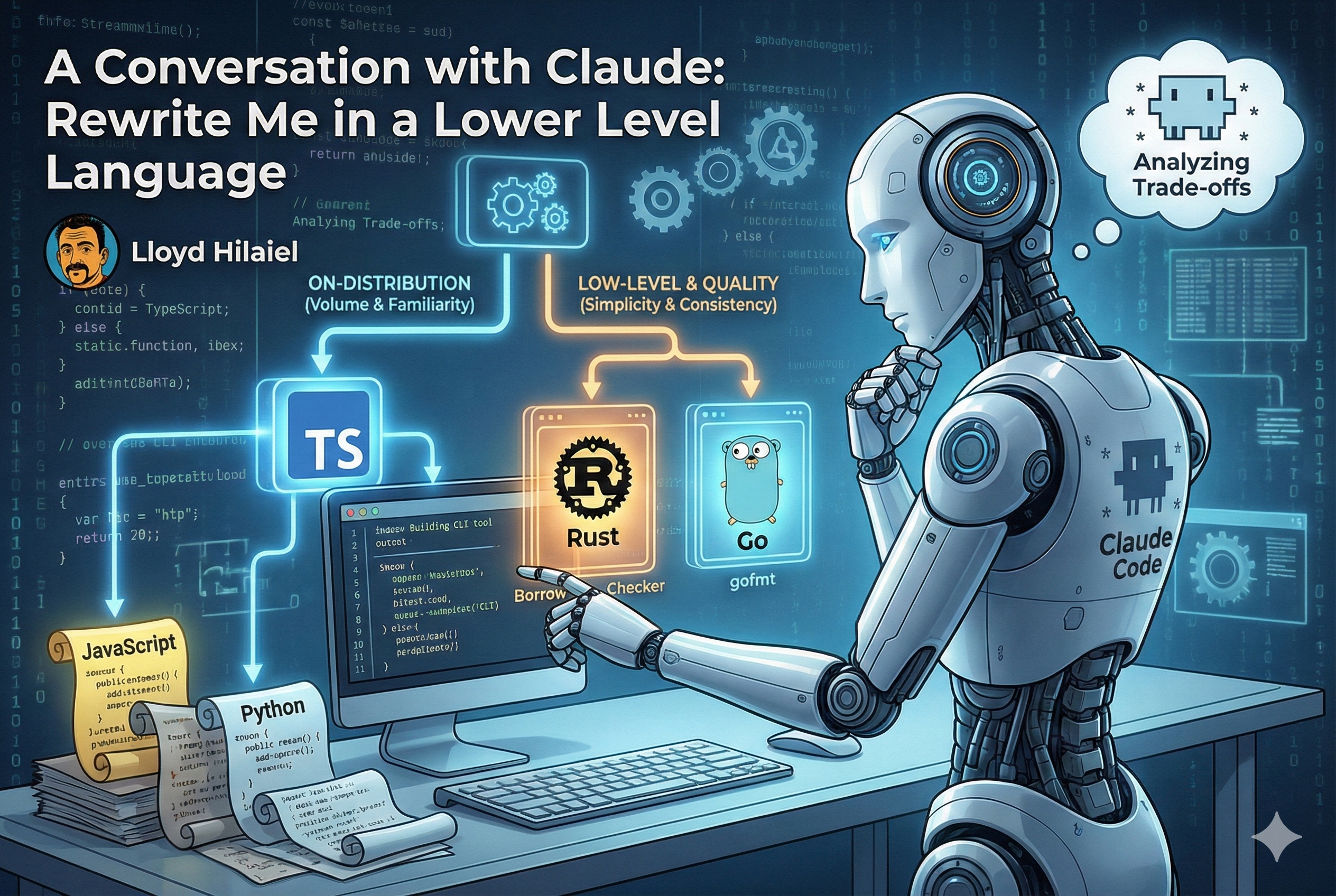

Boris Cherny, the founding engineer of Claude Code, made a counterintuitive decision when building Anthropic’s CLI tool: TypeScript and React. Not because they’re the “best” languages in some abstract sense, but because of a concept he calls being “on-distribution.”

In interviews, Boris has explained that they wanted a tech stack Claude was already strong at, so that Claude Code could essentially build itself. The claim is remarkable: approximately 90% of Claude Code was written using Claude Code. This creates a virtuous cycle—the tool improves at building tools like itself.

The alternative, an “off-distribution” stack, would require teaching the model “the ropes.” You’d spend cycles bootstrapping competency instead of shipping features.

But here’s what’s interesting: this reasoning goes deeper than just “lots of TypeScript exists in the training data.” If raw volume were the only factor, JavaScript would dominate everything. The real insight is about quality distribution—and what happens when a language’s corpus contains too much bad code.

The Conversation

This got me thinking. I asked Claude Code directly about the tension between language popularity, code quality, and structural simplicity. Here’s what happened:

Lloyd: You are Claude Code. You know how to engineer software! My question is to you: what languages are you best at? Logic suggests that whatever languages have:

- The simplest, clearest structure (smaller scope of language and fewer ways to do it suggest fewer training examples needed)

- The volume of code publicly available that you have access to

- The average quality of code examples

So on the one hand, you want a language with LOTS of examples (i.e., JavaScript, TypeScript). But on the other hand you want a language that is small and tight and very carefully engineered to have minimal meaningless variation (i.e., Go—I love Russ Cox—but not JavaScript, where Crockford had to pick 20% of the language that doesn’t suck). And on the other hand you want a language that is NOT a learner language, NOT accessible to people with fewer years in the trade (i.e., NOT JavaScript and Python, because LOTS of bad code exists).

SO! Analyze this thinking and riddle me: If I were to want a programming language that was an excellent balance of low level (for speed and efficiency) and Claude competency (you’re great at), what is the ideal choice?

Claude: Great framework. Let me work through it honestly:

The Tension You’ve Identified

| Factor | Winners |

|---|---|

| Volume | Python, JS/TS, Java |

| Simplicity/Consistency | Go, C |

| Code Quality (avg) | Rust, Go, Haskell |

For Low-Level + Claude Competency

My answer: Rust

Here’s why it threads your needle:

- Low-level: Zero-cost abstractions, no GC, systems programming capable

- Code quality filter built-in: The borrow checker rejects bad code. Code that compiles has already passed a quality gate. This means the training corpus is pre-filtered.

- Not a learner language: The learning curve keeps out casual coders. The average Rust author has years of experience.

- Consistency: rustfmt + strong conventions. Clippy lints enforce idioms.

- Documentation culture: Rust has unusually good docs/examples (docs.rs, the book, etc.)

Runner-up: Go

If “low-level enough” works (it’s not bare metal, but it’s fast):

- gofmt means ONE way to format code—zero style noise

- Russ Cox’s minimalism = tiny language surface

- Corporate-quality codebases (Google, Cloudflare, etc.)

- Simpler than Rust = I make fewer mistakes

Honest Assessment

I’m genuinely strong at both. Rust’s strictness means when I write code that compiles, it’s usually correct. Go’s simplicity means there’s less to get wrong.

If you need true low-level: Rust

If you need “fast enough” with maximum reliability from me: Go

The Counter-Example Problem

What struck me about this exchange is Claude’s point about Rust’s borrow checker acting as a quality filter on the training corpus itself. Bad Rust code doesn’t compile. It never makes it into repositories. It never becomes a training example.

Contrast this with JavaScript or Python, where syntactically valid but semantically horrific code is everywhere. Every “Learn to Code in 30 Days” tutorial, every Stack Overflow answer optimized for upvotes over correctness, every quick script someone pushed to GitHub and forgot—it all becomes training signal.

This is the insight Boris’s “on-distribution” framing partially captures but doesn’t fully articulate: it’s not just about volume, it’s about the ratio of good examples to bad examples.

A language can have:

- High volume, high quality ratio (TypeScript in well-maintained corporate codebases)

- High volume, low quality ratio (vanilla JavaScript across the entire web)

- Low volume, high quality ratio (Rust, Haskell)

- Low volume, low quality ratio (obscure DSLs)

The sweet spot isn’t maximum volume. It’s maximum good volume with minimum bad volume.

Why This Matters

If you’re building something where AI assistance will be central to your workflow, language choice isn’t just about your team’s preferences or the ecosystem’s maturity. It’s about how well the AI can help you.

Boris chose TypeScript because Claude is good at TypeScript and he wanted Claude to build Claude Code. That’s a legitimate strategy: play to your strengths.

But if you’re starting fresh and want to optimize for AI-assisted development in a lower-level context, Claude’s self-assessment points toward Rust or Go. Not because they have the most examples, but because they have the best examples—either through compiler-enforced quality (Rust) or through opinionated simplicity (Go).

The language you choose shapes not just how you write code, but how well your AI collaborator can help you write it.

lloyd