A couple days ago I finished a run and set the title in Strava—a moment later I was presented with a silly AI summary. Cute. Useless. And emblematic of a bigger trend: every product team is racing to bolt an AI assistant onto their surface. Meanwhile, the work I want done starts above any single app and crosses all of them.

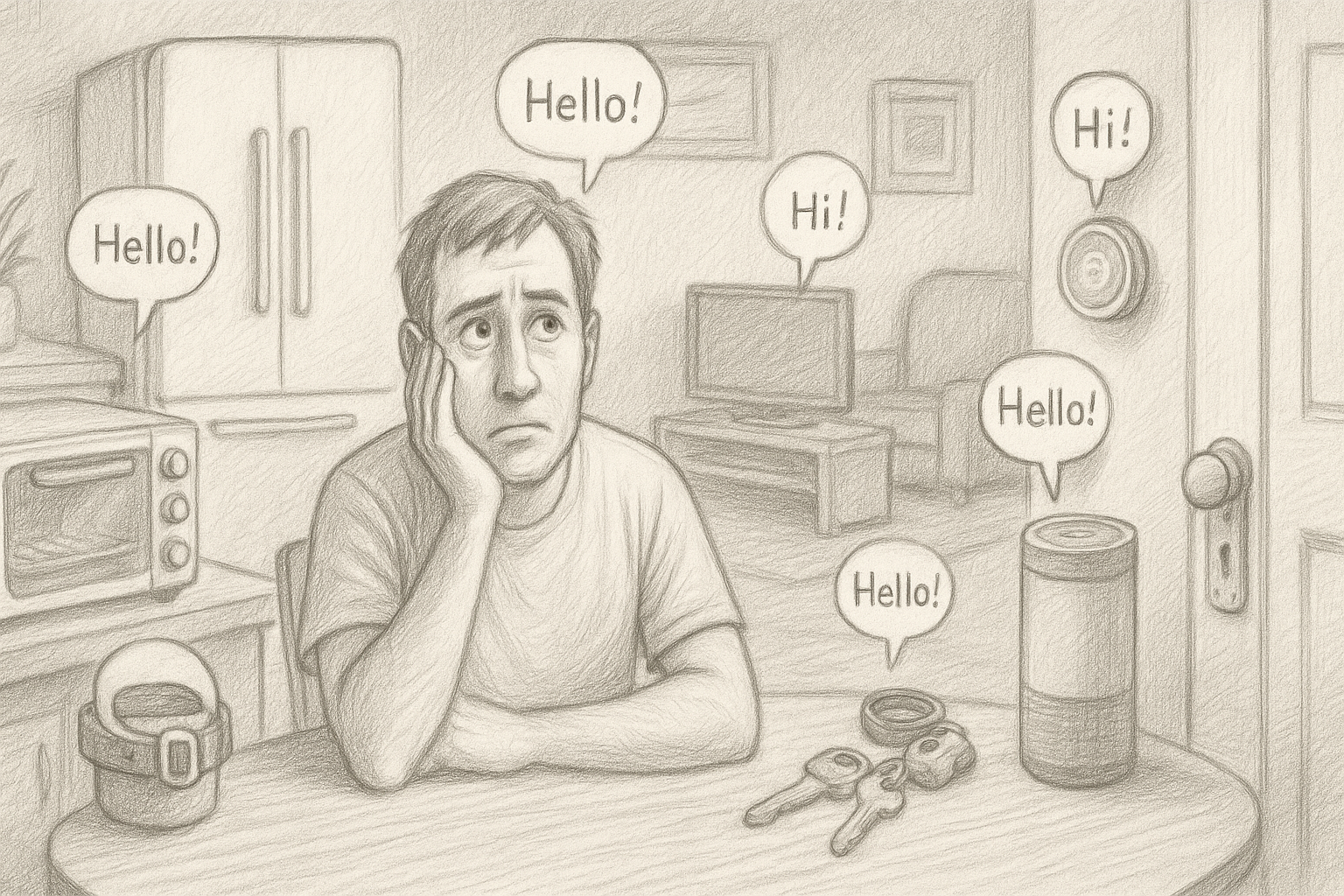

Let’s stop pretending the interface we should talk to lives inside every silo. It doesn’t. AI assistants belong to the user’s agent—the thing that knows our world, our preferences, our data—not embedded per-app.

The pattern behind the hype (and why it breaks)

- Context lives across silos. Real tasks (“retrieve that recent email from my ex, summarize my expenditures on our property in early 2024, and fact check her assertions”) braid together files, mail, calendar, and notes.

- Preference & memory sprawl. Ten mini-assistants each want their own persona, settings, and memory. I want one brain that learns me once.

- Redundant R&D, brittle UX. Per-app AI assistants are expensive to build, hard to maintain, and never as capable as a user-chosen agent with proper tools.

If you’re building an AI assistant into a single product, ask: Am I a data source, or am I the primary actor the user truly wants to talk to? Most apps are sources. That’s not an insult; it’s a design truth.

Exhibit A through E: nice demos, wrong layer

A) Adobe Acrobat: “talk to your PDF”

Acrobat’s AI Assistant now supports hands-free voice in its app and “PDF Spaces.” You can literally talk to a document viewer, ask questions, and get spoken responses.

Why this misses: PDF is just syntax—packaging for content. The information I need lives as conversations in Slack, documents across Word/PDF/web, and scattered emails. I need to reason across all of it, not chat with one file format. Nobody cares about “PDFs”—they care about understanding the full context of their information, wherever it lives.

B) Google Photos “Ask Photos”: chat with your memories

Ask Photos is a conversational way to query your photo library—”show me the best picture from each national park I visited.”

Why this misses: My memories aren’t only in Google Photos. They’re fragmented across text exchanges, WhatsApp conversations, my iPhone camera roll, Instagram posts, DMs, and social media. To find that one photo, I might need to cross-reference my social accounts to pinpoint when I was at a location. And once I find it? I need to share it, enhance it with my choice of AI, or print it with my preferred provider. “Chat with your memories” is a broken promise when it only sees one silo.

C) Spotify DJ: hold to talk to the DJ

The AI DJ now takes real-time voice requests in many markets for Premium users. Hold the button, speak a mood/genre, the DJ adapts.

Why this misses: Spotify provides two things—access to music and recommendations. But countless times on my run, I hear something in an automatic mix that I later want to recall. My primary agent—the one I talk to most—is what I’ll ask to “queue up the top 5 most popular songs from the Sweet Lillies for my next trail run.” That needs to work whether my music dollars go to Spotify, Apple, or Amazon. The assistant should be mine, not theirs.

D) Zoom AI Companion: another assistant in the meeting window

Zoom lets participants ask in-meeting questions grounded in the live transcript.

Why this misses: This fails for the same reason “talk to your PDF” does. The Zoom meeting is just another event, another piece of knowledge—data I want to remember and query, not a destination. I might have a meeting, a PDF, and an email thread that together comprise the ground truth for a decision I need to make. The most interesting part about any meeting is all the context around it—the prep docs, related emails, follow-up commitments—not the meeting transcript itself.

E) GitHub “Copilot Voice”: a cautionary tale

GitHub ended the specialized “Hey, GitHub!” voice preview and handed speech to the generic VS Code speech extension.

Why this teaches the lesson: maintaining AI assistants per surface is brittle. The durable value concentrates at the agent layer that spans repos, issues, docs, and chat—not one editor.

What good looks like

One agent. Many tools. Zero silos.

The thing I talk to should be mine: latest-gen model, my privacy posture (including on-device when I want it), my visualization stack (diagrams, charts), my long-term memory, and my connections—email, files, calendar, chat, repos, analytics, bank feeds, health, you name it.

Vendors should ship tools and authenticated access, not their own AI overlord:

- Expose capabilities as tools (query, fetch, mutate) with clear schemas and scopes.

- Standardize auth so my agent can connect once and rotate tokens sanely.

- Return structured, composable data (not just prose) so my agent can fuse and visualize.

- Stay opinionated at the source (great analytics! great file diffs!) while resisting “agent-cosplay.”

Call it MCP-ish if you like; call it “tools over assistants.” The point is the same: apps provide data and actions; the agent provides the conversation and the plan.

A quick design test for builders

-

Are you a destination or a datasource?

If most valuable user intents require other systems, you’re a source—optimize for tools and access, not owning the AI assistant. -

Does your AI assistant meaningfully outperform the user’s agent with your tools attached?

If not, you’re adding redundant UX and maintenance. -

Will your per-app memory and visualization choices scale to user preference?

Probably not. Let the agent own preference, you own truth and capability.

The industry nudge (a friendly one)

Big players building user-agents should align on auth and capability schemas so we don’t recreate the streaming-app mess for AI. Vendors who resist will ship louder demos and worse outcomes. Vendors who cooperate will ship fewer UIs and better user value.

We can still ship “starter” AI assistants inside products for debugging and testing your tools. Just don’t confuse that with the endgame. The endgame is simple:

Let my agent talk.

Let your app do.